After my second trip to the Stratford Festival (theatrejones.com published my thoughts on the nine productions I saw here), I almost immediately began suffering with withdrawal symptoms.

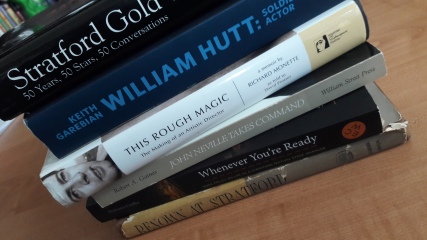

A good thing, then, that I had a couple of books about the festival that i picked up on the trip.

And that they led me to more.

And them to more, making up much of the reading pile for my Shakespeare summer.

I’ll start with my most recent acquisition: A beat up copy of “Renown at Stratford” (Clarke, Irwin & Company) found via the terrific online used book outlet Discoverybooks.com.

Published in 1953, it offers a front row look at the first season of the festival, with essays penned by Tyrone Guthrie, Stratford’s first artistic director, and Robertson Davies, one of Canada’s most prominent novelists.

Guthrie gives us the history, told with style, humility, insight and humor. He shares how Stratford local Tom Patterson returned from his military stint in Europe with his eyes opened to the arts. “His perseverance was indomitable,” writes Guthrie, “His enthusiasm, boring to most, infected a few.”

Those few formed a committee and decided to bring in Guthrie, one of the best-known directors in the world, to consider this ambitious project.

“I expected that this would consist mainly of artistic and excitable elderly ladies of both sexes, with a sprinkling of Business Men to restrain the Artistic People from spending money. There would also be an Anxious Nonentity from the Town Hall briefed to see that no municipal funds were promised, but also to see that, if any success were achieved, the municipality would get plenty of credit.”

Guthrie was shocked, instead, to find unanimity in the townsfolk’s support of a festival. They decided to explore a tent theater intimately connecting audience to actors, accepted the idea that making back costs even within two years was unlikely, opted for two productions in the first season, and pushed for a cast that would primarily be Canadian with a limited number of others joining the ranks.

All that in the first meeting.

Already I feel like I’m getting wrapped up in details. Allow me to back up a little.

See, I was late to the Stratford party. After an ill-fated effort to partner with a tour company to take a group of Central Indiana folks there a few years back, I finally took a review trip there in 2017. A glorious production of “Twelfth Night,” a fun tour of the costume shop, and an all-hands-on-deck production of “Guys and Dolls” proved the highlights.

I felt not only like I was seeing terrific theater, but also that I was seeing rare theater. I’ve seen wonderful Shakespeare productions stateside, but rarely do I feel like I’m getting the full effect. There’s a kick to seeing, say, five actors performing “King Lear” in an hour and a half and clarity certainly wins in a “Hamlet” that removes all of the political context. But it’s difficult to fully bask in even the most successful of those truncated shows, especially when created on a limited budget.

From the beginning, Stratford committed itself to quality, bringing in Alec Guinness and Irene Worth to lead that first season’s company in productions of “Richard III” and “All’s Well that Ends Well.”

The second part of “Renown at Stratford” focuses on those two productions, pairing Robertson Davies essays with drawings by Grant MacDonald of costumed cast members. The essays are smart, quirky, and remarkably observant and the illustrations unique in their ability to capture actor attitudes, making this rare book a treasure of my theater collection.

One of the actors illustrated in the book played the small part of Sir Robert Brackenberry in “Richard III.” Of him, Davies writes “The portrait of the actor who played Brackenbury brings to the ear again his voice…It would be unjust to the other Canadian actors in the company to single out one of them for special commendation for his good speaking, but let William Hutt stand for all, like the soldier who receives a decoration in the name of his regiment.”

Little did Davies realize that the actor he singled out would become a Stratford cornerstone and one of Canada’s–hell, the English-speaking world’s–leading actors.

Because of his steady work almost exclusively in Canada, though, Hutt isn’t the theater-geek household name he should be.

While his Prospero, Titus, Tartuffe, and more are the stuff of legend from those north of the border, those elsewhere may only know him from his brilliant turn in the short-run series “Slings and Arrows” as the aging, heroine-addicted actor cast as Lear in the final season. Those with longer memories may have caught his James Tyrone in the Great Performances presentation of “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” in 1995.

Here’s hoping “William Hutt: Soldier Actor” (Guernica) by Keith Garebian, helps place him higher on the international theater radar to the place he, by all accounts, deserves. Garebian’s emptying-the-notebook biography, richly detailed almost to a fault, goes beyond just insight into the World War II hero (hence that half of the title), actor, and man.

Don’t get me wrong. It feels like we learn everything we need to learn about Hutt, his personal conflicts and his artistic challenges.

But, on another level, the book implicitly celebrates the notion of the career stage actor–an actor who, in a single season, can play Uncle Vanya, Don Armado (oh, to have seen Hutt in that that), Richard II, and a batch of other roles. Hutt performed in 12 plays in 1954, another eight the following year, including Macbeth and the Chorus Leader in “Oedipus Rex.” For Hutt, a slow year meant five plays.

Garebian deftly mixes biography with insight into the actor’s craft, analyzing performances while also allowing Hutt to speak for himself.

For example: “A pause that grows into a silence, when he seems to be doing nothing, shows a character thinking, not merely an actor working,” writes Garebian. “However, Hutt knew that actors are also themselves on stage.”

He then quotes Hutt: “I cannot pretend that I am not Bill Hutt on stage, but so long as I wrap myself in the experience and illuminate the audience that it is a different set of circumstances, to them I become a different person. You cannot perform Lear or Timon of Athens; you cannot perform Titus; you cannot perform Hamlet. All you can do is experience those roles.”

The ache of a biography, especially one so packed with ephemeral work, is loss. While his triumphs were many–including his Stratford swan song “Tempest,” the decline in Hutt’s health combined with the knowledge that much of his work is not available for posterity makes the final chapters difficult. Here’s where Garebian’s insight proves most necessary and welcome.

“Almost every major actor at a certain age (Redgrave, Gielgud, Olivier, and others) struggles to preserve a vital capacity for self-renewal and development,” he writes. “Hutt was different. Although he suffered physical afflictions in old age, he maintained his splendid vocal range and much of its power. His Prospero, to the very last word, was clear, distinct, and brilliantly modulated. but his voice was remarkable not only for its range and power; but it also acquired the correct tone for each role because it grew out of his thoughts and emotions as the character. By putting the truth of his feelings and thoughts first, the appropriate sound resulted naturally.”

Sometimes the voice is there but not the words. In one anecdote, Garebian recounts Hutt’s struggles with a playing the title role in the solo show “Clarence Darrow.”

“…there were two or three times when his memory failed. The solution was clever: Nora Polley, his dresser and stage manager, would stand behind a flat, and when he was lost, he would ask: “Where am I, Ruby?” in the most natural of voices, as if Darrow were addressing his late wife and seeking her ghostly help with his life. Then Polley would whisper a line, and the audience never guessed that this was not part of the script.”

In most theatrical biographies, a stage manager, at most, makes a brief anecdotal appearance.

But in what is perhaps the most unique book in my Stratford stack, that same Sarah Polley gets her own book.

“Whenever You’re Ready: Nora Polley on Life as a Stratford Festival Stage Manager” (ECW Press) offers a winning first-person look at this underrepresented but essential theatrical career path.

The authorship is a bit confusing. While told first-person through Polley, the book is credited to writer/actor Shawn DeSouza-Coelho. The rich detail and consistently engaging voice–in conjunction with the unique perspective–makes clear, though. that the reader is being parked in Polley’s heart and head.

That’s key to making “Whenever Your Ready” as much of a page-turner as it is. Polley doesn’t shy away from revealing the challenges of working with a string of artistic directors, each with a different set of expectations and demands. She’s smart, sensitive, playful and professional.

A stage manager–a good one–isn’t always appreciated. Yet they are the ones witnessing every performance, working to insure that audiences three weeks or three months into a run are given a performance as high-level as that of opening night.

She’s moving in her appreciation of both the work on stage and her contribution to it.

Regarding a performance by Martha Henry in the play “Dear Antoine,” Polley says, “From the darkness shrouding the stage, the audience applauded. And, as the actors bowed, I knew it wasn’t for me they clapped. It wasn’t for my closed book, my little lamp, or my tiny desk ghat they poured forth congratulations. Yet, night after night, Martha’s smile made me feel otherwise. night after night, it bridged the gap between my effort and their adulation…”

Among the Stratford artistic directors Polley worked for were John Neville (at the helm from 1985-90) and Richard Monette (1994-2007), each of which has a book devoted to him.

The title gives away some of the limitations of “John Neville Takes Command” by Robert A. Gaines (William Street Press).

In the forward, the author states “…historians must record contemporary events of significance at the time when they occur so that an accurate account, not only of what happened but of why those persons most closely associated with the event believed it happened, can be part of the permanent record.”

Often, though, it comes across as more record than read.

The book kicks off with a solid look at the planning of Neville’s first season–which included a “Hamlet” paired with “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead,” “A Man for All Seasons,” “The Winter’s Tale,” “The Boys from Syracuse” and more. It then takes a show-by-show approach.

The details are plentiful and especially commendable in the appreciation of the work of lighting and set designers. But Gaines’ prioritization of trees over forest made this the only book in the Stratford pile that encouraged me to skim.

The autobiography “This Rough Magic: The Making of an Artistic Director” (Stratford Shakespeare Festival of Canada) is quite different.

A ripping yard primarily covering the days leading up to Richard Monette’s appointment as Stratford’s backstage leading man, it’s filled with memorable tales from his acting days. Those include a lengthy look at the development of the notorious “Oh, Calcutta!” in which Monette–all of him–appeared. There’s also telling insight acquired during his time as a Stratford actor–including a notorious outburst when he publicly challenged the festival’s board of directors.

Rather then go into detail about his tenure at Stratford, he closes the book philosophically.

“Plays on the shelf are literature;” he writes, “only plays on a stage are theater. And a play on a stage without an audience is not a performance; it is only a rehearsal. To keep the doors open, therefore, and to persuade people to pass through them in the greatest possible numbers, is the first and most sacred duty of any artistic director. All else flows from that. If I had done nothing else in my tenure to be proud of, I would be proud of the fact that I have been a ‘people’s director’ who did everything I could to make audiences feel as much at home in the theatres of the Stratford Festival as I do myself.”

Alas, no sequel followed.

If all of this is too specific, there’s “Stratford Gold: 50 Years, 50 Stars, 50 Conversations” with Richard Ouzounian (McArthur & Company). The awkward “with” stems from the fact that the book grew out of a CBC series that the Toronto Star critic produced and hosted.

Brief interviews with festival founder Tom Patterson and theater designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch get things rolling. And while many of the names may be unfamiliar to those who don’t frequent Stratford, you don’t have to go far before finding a familiar name.

There’s Christopher Plummer, the festival’s first Hamlet. And Zoe Caldwell, a Stratford Cleopatra. Len Cariou was a Prospero here. And, prior to journeying to space, the final frontier, William Shatner, he played supporting roles in “Shrew,” “Merchant,” and “Henry V.”

Maggie Smith, Andrew Martin, Hume Cronyn, Eric McCormack, Colm Feore (back next season in “Richard III,” and Alan Bates all share their thoughts.

But it’s the career Stratfordians such as Hutt that I find the most fascinating.

A favorite twice-removed story: Novelist Timothy Findley, who acted in the fest’s first season, shares a story about an experience with William Hutt.

“We had seen a performance of ‘King Lear’ that was awful….hanging on the curtain and real tears at the end of the play with Cordelia and so on. And I said, ‘Bill, why doesn’t that work? Why didn’t it work?’ And Bill said, ‘Well, he just went ‘do re me fa so la ti do,’ but the actor’s real job is to go ‘do re me fa so la ti’ and let the audience go ‘do.'”

“This is something I believe very strongly,” said 20-year-Stratford vet Barry MacGregor, “that if all actors give on a stage, then they all receive. And if they all receive, the audience will receive a hundredfold.”

Ah, to have received more of these performances.

Thank goodness many of them have been preserved, expertly, for movie theater and hope screening. Here’s a piece I wrote for Howlround about the production process. And many of the recent entries in the filmed series can be found at www.broadwayhd.com.

Most memorable William Hutt performance I saw was when he played Lady Bracknell. During the detailed interview with Jack to determine his suitability to enter the family, after the line in which he admits he had been found as an infant in a handbag, Hutt did what could only be called a quadruple take, his face declining in one small jerk after another, down to his/her chest, eyes closed. The audience roared after each slight move, and erupted in laughter and applause at the end of the series. Quite a stagy bit, but so effective.

The fact that you’ve seen more than one Hutt performance makes me very happy for you (I don’t do jealousy). I hope Tom Rooney will be back next season. Loved him in Twelfth Night and in some of the Stratford videos.